Information and data related to climate change are ever-evolving, which means the conversation we have with our communities needs to evolve with them. Taking action to adapt to climate change or mitigate natural hazards is best supported when people can visualize the impact to their home, business, beloved downtown, or favorite coastal summer spot. Therefore, as practitioners, we need to be able to provide local, data-driven models that can illustrate not only the projected impacts of climate change, whether it is sea level rise, increasingly severe storms and associated floods, or urban heat islands, but also the possible suite of solutions.

We have purposely used the phrase ‘suite of solutions’ because in most cases there is not a single silver bullet that will reduce a community’s vulnerability but rather a series of actions implemented over time. With a tremendous amount of the response to climate change being funded by public dollars, we need to be certain that we are investing in solutions that will provide the greatest return on investment.The science behind climate change is clear and localized modeling of existing conditions, future conditions under climate change, and the possible benefits of climate resiliency interventions needs to be a critical component of the information we are providing to the decision makers. Without the data showing the predicted impacts of climate change and the urgency to invest in climate resiliency measures today, many otherwise laudable efforts could be for naught. In this decision-making effort, the proponents of climate change response need to provide easy-to-understand modeling results paired with community-oriented prioritization techniques to illustrate the ultimate benefits of taking action.

Below, we describe a helpful process for creating an environment where decisions can be based on science. This template is written specifically for identifying interventions that will reduce both urban stormwater and riverine flooding, but the eight phases could easily be amended for other climate change threats:

1. Gather information on all existing stormwater infrastructure as a baseline. Stormwater systems typically consist of both piped and natural flows. The first step in our protocol is to review the existing data to become familiar with the system and to identify any data gaps in the municipality’s current information domain. The data are used to develop a stormwater model and assess the proposed climate resilience intervention for other co-benefits later in the prioritization process. Data collection can include reports and studies related to the geographic area of interest (often a watershed or subbasin) and GIS layers of:

- topography and soils

- the stormwater system (pipes, manholes, catch basins, culverts, outfalls)

- other physical features such as roadways and waterways

- parcel information indicating ownership, impervious surface, and land use

- public perceptions of drainage issues, experiences of flooding, and other preliminary input

2. Conduct a thorough field data collection effort. Field reconnaissance efforts not only provide ground-truthing of GIS and other historic information gathered in Step 1 but also fill data gaps such as pipe sizes and elevations. Stream walking surveys can also document stream embankment width/height, areas of erosion, and a review of any potential maintenance issues such as fallen trees, accumulated debris, other sediment deposition patterns that are restricting flow, and any structural deficiencies of headwalls, culverts, or bridges. Site visits, stream cleanups, and walking tours with the community are options for involving the public in this specific step.

3. Model current conditions. Data collection efforts feed directly into the development of a hydrologic and hydraulic model. The model can be used to identify pinch points in the current stormwater system and areas that are likely to flood during specific design storm events. This modeling creates a baseline to compare both climate change projects and the evaluation of impacts of climate resiliency interventions.

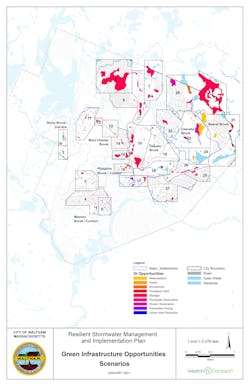

5. Propose interventions and model their impact. Based on the data gathered and modeled in Steps 1–4, the goal of this step is to develop a suite of feasible green infrastructure (GI) or other flood mitigation techniques that could be implemented to alleviate the anticipated impacts of climate change. The objective of identifying resiliency interventions is to upsize any existing pinch points in the system (such as increasing culvert size) or to alleviate capacity concerns through upstream interventions (such as flood storage or infiltration through GI). Oftentimes, the choice of location for these interventions can be narrowed by considering opportunities and constraints, which could include:

- neighborhoods or streets that already frequently flood

- areas with large amounts of impervious surfaces, like parking lots and roads

- parcels that are municipally owned

Interactive mapping of modeling results and proposed interventions are great ways to visualize the future impacts of climate change and the solutions that can improve the community’s resilience.

6. Look for opportunities to include co-benefits. While you are analyzing climate resiliency interventions, you will want to look for opportunities to include co-benefits as a prioritization metric and additional reasons to invest. Co-benefits are positive outcomes that are a result of the proposed intervention above and beyond the main objective. For example, GI best management practices have multiple co-benefits because they recharge groundwater, treat pollutants, and help reduce urban heat island effects. Other co-benefits could include place-making, addressing erosion concerns, enhancing wildlife habitat, and improving aging infrastructure.

7. Prioritize. At this point, with many potential GI options available to reduce projected future flooding, it is time to decide which individual projects will be carried through to implementation and when. This prioritization process can be based upon various factors and values, but some of the more frequent factors include risk reduction, benefits to environmental justice populations, cost, and other co-benefits. Public input on how to prioritize actions or on the actual prioritization is a useful exercise. Oftentimes, interventions have tradeoffs and risks that, if well understood by the community, can lead to improved implementation later.

8. Engage the community throughout the process. Finally, it cannot be stressed enough that it is never too early in the lifecycle of projects to begin engaging with community stakeholders. Throughout the steps above, we have identified several places to engage the community in developing a prioritized list of climate resiliency actions. Transparent and consistent communication with the community will ensure that the final product is reflective of their needs. A community that has been engaged and connected to a project and that believes that its ideas, concerns, and opinions have been heard honestly, early, and often is a community that is more likely to champion further implementation. Targeted stakeholders can include business associations, local opinion leaders, non-profit organizations, residents of environmental justice neighborhoods, elected officials, and other entities that have a direct interest in the outcome of the plan.

Promoting ways to be involved in climate resiliency efforts is just as essential. Examples of effective public engagement tools are:- interactive websites

- social media posts with data visuals and videos

- hard copy flyers and fact sheets posted in high traffic areas

- e-blasts and press releases

- distribution through local community organizations

- signs within the project area or watershed

- surveys

- in-person or virtual meetings (that are fun!)

Climate resilient projects that are informed by data-driven analysis and community input will have a far higher chance of success than those that have been planned behind closed doors. The 8-step method presented above can be tailored to best fit your community’s concerns with additional analysis for specific co-benefits or using the results to create a mini capital improvement plan. SW

Published in Stormwater magazine, August 2021.