Today, the once-ritual Sunday dinner at Grandma’s has largely fallen to the wayside and is a memory of a bygone era. But for those of us who can remember it, the post-meal cleanup after these gastronomic events had specific protocols that recalled Depression-era deprivation and the “waste not, want not” philosophy.

First, all the uneaten cooked food left on the plates was either given to pets or scraped into the kitchen trash bin. Then, bread, cake, and pastry were put out into the yard for birds, and eggshells, vegetable peels, and coffee grounds were distributed on the flower and vegetable garden as being “good for the dirt.” Nobody called it recycling, but in a way it was.

However, with the post-war suburban homebuilding boom, standard installation of garbage disposals did away with some of those messy and “old fashioned” chores. Just about anything went down the disposal, including pieces of jewelry and the occasional fork. And sure, it was fine to put bacon grease and meat drippings in there “as long as you ran hot water with it.”

But those were the days—literally decades—when just about everything went down sink drains, into street curb inlets, and sometimes into ponds and rivers as if “out

of sight, out of mind” was all we needed to know. While we cringe today at the idea, paint, solvents, motor oil, hydraulic fluid, food waste, and more were often disposed of in this way with a perfectly clear conscience. Not a lot of thought was given to the mysteries of these substances’ final destination.

“People had the idea that it all ‘just went somewhere,’ and as long as they got rid of it, that was the end of their responsibility,” says Bill Hodgins, senior water research engineer at the Ellicott City, MD-based nonprofit Center for Watershed Protection (CWP). He adds that in its 26-year history, CWP has expanded its role from working to protect watersheds to becoming a leader in stormwater management and watershed planning and is now “providing guidance to diverse audiences across the country to help them address their needs in these arenas.”

He notes, “We have a specialty in many areas; we’ve done monitoring and recommended BMPs, helped cities with their stormwater design, and assisted communities in finding illegal sewage discharges to waterways.”

Hodgins says that even with increased public awareness about putting bad stuff down drains or into waterways, it’s still a problem, and from his South Carolina CWP office he hears about the problem firsthand and is called in to help.

“Many of these practices still happen, and while we do find intentional and purposeful illegal disposal, in many cases it is the result of being uninformed or from inadvertent plumbing cross connections.”

Investigating sources of illegal discharge in stormwater falls under the purview of many cities’ National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. Hodgins says CWP has assisted municipalities and private owners by providing educational documents and stormwater BMPs that help them comply with the EPA’s guidelines for illicit discharge detection and elimination (IDDE) monitoring programs.

“CWP is focused on helping cities find contaminants and pathogens that not only threaten public health but that also threaten the economy of their revenue stream, such as commercial fishing and seafood operations.”

Coastal areas like his are particularly susceptible to violations as oyster and shellfish harvesting will be closed when any pathogenic contamination is detected.

Hodgins’ office, “almost halfway between Savannah and Charleston,” also gives him the local perspective.

“Communities are pretty vigilant around here because any impaired water bodies directly affect the local pocketbook, as processing and production and related jobs depend on the availability of our seafood bounty.”

Availability of local seafood is a big draw that keeps year-round tourism to the Carolina beaches a thriving source of revenue that, he notes, can’t afford any downtime, so managing stormwater overflows and illegal discharges is on everyone’s front burner.

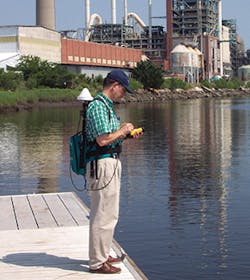

Sampling in coastal waters

Keeping “R” Months Open for Business

“The coastal area is basically a sand dune, and rather than trying to channel overflow to the ocean, it’s better to create surfaces that are permeable so water percolates and filters to the sand underneath,” he explains. “Prior to my coming to the CWP, my work with the City of Savannah included addressing stormwater and the historic streets. We put down a rock subsurface and interlocking permeable pavers, which created the hard surface necessary to drive on but allowed for stormwater infiltration.

“The issues here in this coastal area are primarily due to human waste, either directly from being connected to storm drains through inadvertent plumbing errors or indirectly due to plugs in sanitary causing overflows that make their way to storm drains.”

As a result, the protocols for testing and monitoring have both broad and specific impact, as so many livelihoods depend on water quality.

“For example, if there is a certain amount of rain, 1.5 inches over a certain amount of time, the oyster beds will not be harvested, which is typically done between October 1 to May 15. As the saying goes, this includes nearly all the ‘r’ months, and that’s a long time.”

“When sewage gets into storm drains, the threat is very real for both the communities and our industry, and we have a compelling interest to find out the source of any contaminations. It’s finding these sources that is the tedious and necessary exercise.”

He describes the investigation process as a funnel, “sort of an upsidedown tree with the trunk as the drain at the small end and a network of branches at the large end. Our task, given this configuration, is to go backward up through the funnel, so to speak, and trace through all those branches, one by one, looking for a source of fecal coliform. We have to find out where it first shows up, and this means chasing down each branch looking for the hot spot.

“It could be a failure, which will be visible on the surface, such as a restaurant grease trap that was overflowing and draining in the storm inlet. Other times, we run a camera down through the system to find a cross connection or failure, and with the latest robotics we can work our way visually through the process.”

Hodgins says dye can also be used, but approaching a homeowner in a swanky high-priced neighborhood, often with a registered centuries-old historic home “to ask if we can flush some dye down their toilet” can be a little daunting.

“But typically they understand that what we are trying to do is solve a critical public health issue and are cooperative.”

He also cites a confounding problem that he dubs “legacy bacteria.” “This is bacteria that we can’t easily find; sometimes it’s hard to understand the life of these pathogens.

“In one instance, for example, an E. coli [Escherichia coli] contamination was found in our local community. However, when the suspected detention pond was tested, officials didn’t find any pathogens coming out of it, yet 1,000 feet downstream we found bacteria.

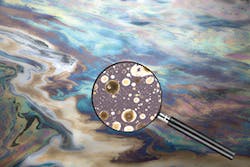

“What we think happens is that sediment in the pond floor harbors the bacteria and then as that sediment is disturbed and carried downstream it comes to life, so to speak, and then the waters test positive. We know that bacteria are in the sediment and that sediments potentially harbor large reservoirs of fecal bacteria, including indicator groups like fecal coliforms and enterococci that are commonly used to identify the presence of fecal contamination. But it makes diagnosing the source difficult.”

The increase in extreme storms, sea level rise, and changes in the climate “complicate things to cope with the effects on stormwater management,” he says.

“I think as a country we have made great progress in stormwater quality through the years. Stormwater management is going to be a challenge that will be with us for some time. All the MS4 communities are well aware of the need to implement testing and monitoring toward IDDE issues, and under their permits, they must implement necessary programs. However, in smaller areas with fewer resources, knowing the problem and having the funds to do something about it is an ongoing dilemma. The local tax base cannot always provide sufficient capital in trained personnel or testing equipment, yet no one can risk a public health crisis either.”

Development Clogging up the Works

Up the coast from Hodgin’s office, “business is booming,” says Hillary Repik, stormwater manager for Mt. Pleasant, SC, a coastal suburb of 80,000 just a few miles away from historic Charleston.

“Last year we had a banner year,” she says, “and we are one of the country’s fastest-growing communities—everyone wants to be near water and Charleston. But new construction and renovation bring real headaches in terms of illegal stormwater discharges.”

Because the area has mostly newer residential and business structures, in contrast to the historic areas of downtown Charleston, “We see fewer illegal or improper cross connections, and our IDDE concerns are more related to incidental dumping and bad housekeeping practices.”

Repik says that every phase of building has the ability to affect water quality in one way or another, but the big culprits for the city’s stormwater concerns are concrete materials and paint.

“During cleanup, or with concrete in the building phases, instead of washing in containment, materials are often spilled on the roads and then simply hosed into the streets when workers are cleaning up. They wash their brushes and other equipment onsite, and this all finds its way to storm inlets.”

She says the city’s inspectors work hard to ensure construction-site controls are in place, but sometimes the word does not get down to the people working on smaller home repairs.

“We’ve also seen evidence of people washing up directly right into the marsh at the water’s edge. Some of this is the old out of sight, out of mind attitude, but clearly going to a marsh and washing up in a wetland is purposeful, illegal contamination.”

To address the paint problem, Repik says, the city has created flyers and distributes them to anyone who has a business license for painting. “We’ve also talked to homeowner groups whose members may hire contractors to tell them about the risks not only of contaminating the water but of damaging our fragile coastal ecosystems, as it affects the viability of our valuable seafood industry.”

Citing other sources that contribute to bacteria contamination, Repik says inspectors occasionally find septic systems that are not properly maintained. All new construction is required to be on the local sewer system.

“Several area creeks have become popular recreation areas. Having clean water for recreation is important to the health and economy of our community,” she says. “We also find that people are trying to be responsible by picking up pet waste, but then they throw it down the storm drain, and this is a huge problem. Really, it’s all about people understanding where water goes. In a lot of cases, it’s not intentional contamination but comes from a lack of awareness on the connection between our land, waters, and our food chain.”

In mid-2018 the town council issued a ban on plastics and Styrofoam, which will take effect in January 2019, “so people have time to use up their existing supplies,” she says.

“The crabs and shrimp that live in our marshes can eat the microplastics and be impacted by anything else that ends up in our creeks, like paint, floor wax, and bacteria, so we have to reduce and eliminate these discharges from the crab or shrimp’s diet to protect the food web up through human consumption.”

Repik stresses that, as in Hodgins’s region, the revenue stream of the seafood industry is dependent on clean water sources and is quickly affected by illegal discharges.

“Most of the IDDE issues have a more direct impact on our natural resources and tourism than on drinking water,” she says.

Repik explains that the drinking water and sanitary sewer are handled by two different Mt. Pleasant agencies. Drinking water comes from the deep Middendorf aquifer, which according to the US Geological Survey is about 45,000 years old.

“This is water that has been filtering a long time and is pumped up and then treated for drinking water,” she notes.

“Problems definitely spike when we have rain, and we’ve started to do DNA sampling so we can find the nonpoint-source IDDEs. We screen for human waste, dogs, and we’re now looking at deer. We have 18 different creeks that feed to our marshes and coast, and we have four inspectors whose job it is to go out to monitor new- and post-construction practices designed to protect the systems and what’s coming out of the nearby outfalls. They focus on our priority watersheds, but because we have both tidewater and groundwater flows moving through our networks, we always have water coming out, so instead of screening for dry-weather flows we look for color and odor indicators before we pull samples.”

However, another side effect of the area’s development gave rise to what she says is one the more challenging IDDE offenders.

Coping With French Fries and Funnel Cakes

“Food trucks are our newest challenge,” says Repik. “We love the trucks for the convenience and service they provide workers at all our new building projects, visitors from year-round tourism, and communities patronizing our outdoor local events. However, we have had several reports and sightings of trucks cleaning out their kitchens into parking lot drainage areas.”

She adds, “Keep in mind that we are a year-round outdoor community so these food trucks service a large number of customer populations every day, but we’ve discovered that they can be a source of pollution into our systems.”

Repik says the vendors’ overriding concern is compliance with food safety regulations, and this requires them “to keep their kitchens clean and grease free.” But at the same time, if the vendors don’t have a good washing-up system, she says, they just wash the kitchen out the back door and into the storm drain.

“Then we get grease and soap in our storm drains. We’re looking at how to help the trucks manage the grease, which is the biggest concern. The issue stems from how the truck is designed; they don’t seem to have a way to manage or collect the water from cleaning their kitchens. Once they get a food truck permit and comply with health and food safety, that is their first goal to keep in operation. Managing the wash water disposal and grease disposal is a secondary concern, if one at all.”

The town is now hoping to work with other water and sewer agencies to help provide advice and education on the problems of grease disposal and wash water, and Repik says Mt. Pleasant is looking for disposal sites that might take the spent grease products and wash water.

“These trucks are part of our community, so it’s important we engage the vendors’ interest in participating with responsible disposal to retain their business and also inform them why pouring it [grease] down the drains can have disastrous effects.”

She adds that she is lucky to have a “dedicated and hard-working staff who will drop what they are doing to chase down an IDDE report of paint, concrete, or another discharge.

“We have found a big lesson learned is that the cost of cleanup is so much higher; if we can prevent pollutants from getting into the system in the first place, we are much further ahead, both financially and environmentally, which is where our education comes in.”

But if they do find that paint, for example, has already been dumped in a storm drain, her fast-acting staff can get to it immediately “before it rains if possible.”

She says, “If we can keep it in the drain, and by using our maps to find where we can plug off other areas while we remove it, we’ve protected our watershed.”

A submerged storm sewer discharging a plume of unknown material

Sweet Treats Reveal IDDE Culprits

Madison, WI, a city of about 300,000, has an unusual geography. Situated between two connected lakes, the Monona and the Mendota, with just over a mile between the two of them, there is literally water everywhere. And as such, says public health environmental protection lead worker Rick Wenta, “Most of our downtown storm sewers are partially submerged. So even in drought situations we still have standing water in our storm pipes.”

He notes, “The health department has been vigilant in enforcing regulations against illegal dumping since 1974, and we’ve been coping with the gamut of illicit substances—from carpet cleaning wastewater to vandalized restaurant grease collection barrels and everything in between.”

Wenta says Public Health Madison and Dane County (PHMDC) got involved in IDDE after an ordinance was passed on monitoring and testing for all NPDES Phase I permittees. The area’s storm sewer system now conveys stormwater to about 300 outfalls destined for Lakes Mendota, Monona, and Wingra.

However, when high levels of indicator bacteria were detected “early on in our program,” says Wenta, “we naturally assumed that this was the result of cross connections that are sometimes inadvertently created and not discovered during repairs of the aging pipe infrastructure.”

He explains that these connections can develop when old buildings, “such as a gas station, for example, that had a floor drain and literally everything went down that drain,” gets a new plumbing upgrade 60 years later. The modern-day plumber is likely unaware that the old floor drain was originally connected to the storm system, and when an upgrade is installed would naturally tie the sanitary lines to what was originally storm drain.

“Given these circumstances and the age of our city, we had set some conservative thresholds in the early days of our program. And, since we always have water in the partially submerged pipes, we at first thought that the E. coli detected was from cross connections, since no other illegal discharge could be found.”

But he recalls one case where bacterial levels were not the result of a cross connection, and it took some ingenious detective work to identify the culprit, or in this case, the family of culprits.

“I had workers chasing all kinds of imaginary leaks with smoke tests, camera inspections, you name it. We went through a whole pile of tests including fluoride tests to see if it was city water. But we had false positives for fluoride, and the staff running the smoke tests were seeing raccoons.

“This was a pretty low-tech analysis, but it all started to make sense. So we hung marshmallows on strings in the middle of the pipes, and when they were gone, we said, ‘Yep, it’s raccoons.’ So, mystery solved; no point in any more checking.”

Other discharges, he says, are done under furtive cover to avoid detection.

“You don’t think about it, but carpet cleaners use a few hundred gallons of water and it’s full of pretty grimy, unpleasant stuff, and they can park over a curb inlet and simply run their discharge pipe down there. They’re hard to catch, so we are trying to educate operators that this really hurts our lakes and waterways, and we also now tell homeowners to question cleaners on how they plan to dispose of the effluent.”

He adds, “If cleaners don’t want to run the wastewater down to the shop for disposal, we’ve told them it can go down the toilet or sink at the customer’s, but then they say the homeowner might hold them liable for some future plumbing problem. So it is easy to just try and dump it away if no one is looking.”

In another horrific scenario, Wenta describes how vandals knocked over grease barrels, causing hundreds of gallons of spent food grease to enter the system. Now, to prevent vandalism, the health department requires that 50-gallon grease barrels from food services have a locking ring lid and that they be chained to a concrete post or otherwise secured.

Several years ago, in a push to give more teeth to IDDE efforts, Wenta asked for a better enforcement process. “So we went to ticket-writing, and if you get second and third violations, the prices increase.”

Wenta also formalized the training on IDDE observation. “Inspectors typically learned about discharges from on-the-job experience. You would go out with the lead investigator and visually inspect for IDDEs, and eventually, you knew from firsthand observation of color and odor or other attributes where a problem might exist at an outfall. This is valuable but is pretty unscientific.

“I put everything down in writing, describing the types of discharges, what they might look and smell like, and what color denotes a contamination or bacteria. This also helps identify what is a critical problem or public health threat that needs immediate attention or remediation. Inspectors now have accurate guidance so they can take swift, conclusive actions in the field.”

Having analytical chemistry and water resources education is also essential to his department objectives.

“We know that there are businesses that are doing the right thing and are in compliance, and they report others who are not. But the more quickly we can respond to these violation calls with hard evidence, the more we can convert those violators to responsible actions.

“The other part of this is responsiveness to prevent an illegal discharge from reaching the lakes. If we hear about and can immediately confirm a problem exists, the faster we can get city vactor units out and prevent the contaminant from reaching our lakes.”

Wenta affirms that the staff has made some great progress since 2013 when the ticket-writing protocol went into place and they began an outreach program for concrete contractors.

“This has really helped them learn why washing up and disposing down the storm drain or other inappropriate places is a bad idea. Our staff outreach has paid off, and now we’re seeing concrete contractors really paying attention to containment. It’s not easy to change behavior from the path of least resistance to one that takes forethought and planning. But the message, ‘We all live downstream,’ is starting to sink in, and that’s progress.”

A preferable system is for contractors to wash their flumes out into a box that has filter fabric, and when the concrete eventually dries they can recycle it.

Wenta also collaborates with the city’s Engineering Department. Engineer Greg Fries elaborates on that agency’s role.

The health department, says Fries, “does most of the legwork, but they will involve Engineering if camera work of a pipe is needed or if cleanup, such as vactoring, is required.”

He adds, “Here at Engineering, our staff completes dry-weather inspections of one-quarter of our lines annually to check for cross connections. Health also leads a permit program of non-storm discharge to the storm system.”

Fries says Madison is one of the two original Phase I stormwater permittees in Wisconsin. “In the mid-’90s, we got the federal mandate to also do dry-weather testing—except we don’t have dry-weather testing since in a whole section of our city the storm sewer lines are partially submerged. Then it becomes a question of is it lake water or is it a discharge? It’s hard to know.”

He confirms that the issues with concrete contractors pose serious threats to the watershed. “Both our erosion control permits and Health’s enforcement have been stepped up to address this issue,” he says.

“We rarely catch people in the process of dumping an illicit discharge, so we rely on observation reports. The concrete that gets into the system from washing up tools and dumping leftover mixes can be serious. This is a highly alkaline substance and not what we want to alter natural water pH.”

He also cites one aspect of the IDDE oversight as necessary but potentially unpleasant.

“While Engineering does most of the cleanup work with our operations staff and their vactors and booms, Rick and his group have the task of having to drop whatever they are doing to confront intentional violators, sometimes in the process of their doing it. You can imagine acting in this enforcement capacity has its risks and tensions. Plus, they have to follow up to make sure compliance is met. It’s a demanding but necessary component to ensure we protect our waters.”

Conference Consensus and Wish List

In August of this year, the University of Wisconsin, the US Geological Survey, and the Water Environment Federation hosted a Knowledge Development Forum to identify concerns and discuss current issues related to detection of sewage contamination. Deb Caraco, senior water resources engineer and IDDE specialist with the Center for Watershed Protection, shares some impressions from this meeting, as well as her experience.

“As technologies improve and more research is being done, we are developing more reliable protocols to find illicit discharges, but we still need to understand the best ways that communities can apply this research. We will always be improving techniques to identify illicit discharges, but the most sensitive and accurate measures aren’t always needed,” says Caraco.

She explains that bacteria DNA source tracking, which can identify human sources of bacteria at very low concentrations, has improved very quickly as DNA sequencing technologies have improved. However, this specialized and highly sensitive method is much more expensive than traditional chemical monitoring methods used by most communities, and results take much longer.

While these types of advanced techniques are very useful in some situations, their expense can pose a financial challenge for communities in many cases, and they also are not able to identify non-sewage sources of contamination such as wash water or industrial discharges.

“Overall, our chemical monitoring tests are quite reliable at outfalls, and they can be supplemented with some other instream monitoring techniques such as using fluorescence, which helps identify sewage sources. However, these techniques become less reliable for mixed discharges, or in mixed systems where a discharge may be diluted by groundwater. Currently, we don’t have good guidance about when to use more powerful techniques that can identify these hard-to-find discharges.”

What is missing at the moment, and something that Caraco says is at the top of her wish list, is a set of guidance that investigators can refer to as a “decision algorithm” of sorts to help in that selection process.

“As DNA technology continues to leap forward and become more precise, we really need a flowchart to refer people to when they are faced with a complex discharge scenario and can’t find the source,” she says.

“In a large city system you can observe contaminants, but this can be a combination of things coming from different sources and hard to tell the individual discrete factors. In a smaller system, where each pipe has a smaller drainage area, there are usually some indicators such as high ammonia or detergent surfactants, and some of these can be tested onsite. Other tests are typically done in a drinking water lab and you can get your results in a few hours.”

Participants in the forum also discussed other testing options.

“Some communities and nonprofits have been experimenting with using dogs that are specially trained to sniff out sewage and pick out certain contaminants,” she says. Not unlike the airport canines trained for specific olfactory markers, these dogs also have a high level of accuracy. “When they did this work in Wisconsin and compared the dogs to other tests, the dogs were 75% accurate,” says Caraco.

She adds that one advantage to canines is that they are helpful in pinpointing the most likely location of a discharge quickly compared to other techniques because they are able to detect sewage simply by sense of smell.

Summarizing two of the big takeaway messages, Caraco says that she would like to see a synthesis of all the different testing techniques and then something akin to a rating system with companion guidance.

“This would help determine what test to use under what kinds of circumstances to deliver the results you need,” she says.

“The second item on my wish list is that we need to emulate the technology industry. When they introduce a new software, they form user groups and then people test the software and report how well, and under what circumstances, it performed best. For us in water protection, I would like to see a forum of sorts where communities try out different tests and then report back on what they used and why. Conversely, if they didn’t use it, what was the decision behind that? Was it lack of funds, low interest, low impact? This type of systematic input would help to improve guidance over time.”

For discharges that originate from individual properties, such as cross connections, she says, “Most people don’t know there is a problem and they are happy to try and fix it. There are probably a lot more day-to-day problems coming from this sector than those that are intentionally performing illegal discharges.”