It was a series of storms in north Florida in 1957 that led Robert J. Barrett, along with engineers from the University of Florida, to develop the first genuine geosynthetic material. It was used to protect the beaches from erosion. Barrett, president of Carthage Mills who would later become known as the “father of filter fabrics,” would be proud to see how far his development has come. Geosynthetics now do much more than hold back sand. They help build bridges, provide roads in areas previously unmanageable, and help with stormwater management. They’re providing students in Florida a serene study area that was once just cold concrete, and they provide an area for roots to thrive on a roof in Nashville.

Blue Skies—and Floors—in Florida

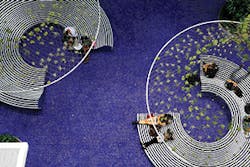

When Mark B. Rosenberg, president of Florida International University (FIU), sought a transformation of the overlooked Deuxieme Maison (DM) courtyard, he didn’t have far to look. Associate professor and landscape architect chair Roberto Rovira met the challenge with a team of design students enrolled at FIU. Students Jose Alvarez, Luis Jimenez, Martina Gonzalez, and Mario Menendez worked alongside Rovira to design the new space that was later dubbed the “Sky Lounge.”

“The university is always really interested in branding its colors, and the blue glass seemed like a strong yet subtle way of celebrating that wish without using a logo per se,” Rovira explains. “The glass is actually crushed SKYY vodka bottles, though we didn’t know this at first and it wasn’t why I christened it the Sky Lounge.” The name came about because nets within the space frame the sky above, and the vine growing on the adjacent walls is known as skyvine (Thunbergia grandiflora). “The name and the source were a funny coincidence,” he says.

The project began in 2010 with a construction cost of $232,000. The team drew on the knowledge from students in landscape, interior design, and architectural design. Rovira has stated that the Sky Lounge demonstrates the power of design, “particularly the power of landscape architecture, which is about strong visions and bold ideas.”

Referred to as Brutalism, the architectural style that previously dominated the DM building was popular from the 1950s through the 1970s. The style of the late 20th century is characterized by heavy “fortress-like” concrete structures and is often labeled as “cold.” Many North American universities and governmental institutions used the Brutalistic style, as it was said to convey strength and functionality. But cold concrete alone is—well, cold. Many of these buildings are now being renovated, and stucco, rock facing, other elements are used to help lighten and brighten the environments.

The FIU student team lightened the lounge with stainless steel structures and nets that hang high from the ceiling. Covering the nets are more than 3,000 air plants and vines that will continue to thrive and fill in the space. These elevated structures work to complement the Grecian blue ground floor in the courtyard. And although the plants are called “air” plants, the vines have a misting irrigation system to provide the small of water necessary.

The flooring at the lounge is what made the design come together. Made from Invisible Structures’ Gravelpave2 and filled with crushed SKYY vodka bottles, the floor provides beauty and a permeable surface for the water to move through.

“The Gravelpave2 made the use of the porous crushed glass solution viable as an ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act]-accessible surface,” says Rovira. “Since I had seen it used at the September 11 memorial at the Pentagon, it felt like the right durable solution that would concurrently ensure accessibility. One of the other attractive aspects of the Gravelpave2 system is that the PVC circles, which are normally hidden but which we intentionally exposed by making them flush with the top of the crushed glass, worked quite well with the circular design features of the space. The custom-designed benches and planters and the braided stainless steel nets that hold over 3,000 air plants above all work very well together.”

Material from a local crushing operation was used as infill for this “floating road.”

Jim Piersol, principal architect of record with Miami-based MC Harry and Associates Inc., explains that the crushed glass was first rolled and polished, then brushed into the geogrid cells. “It was a unique design used with a basic product. It just happened that there was a side benefit. The air plants have a misting system, so the water had to go somewhere. It just so happened that with this product, we solved that problem as well.”

Miami Dade construction company Stobs Brothers performed the installation and construction. Project manager Barry Stevenson explains more about the blue glass.

“The recycled blue glass was purchased from TriVitro Corporation. It is delivered to the site in 50-pound plastic bags. We installed 280 bags of glass. After the Gravelpave2 was fastened in place, the glass was poured onto the surface and broomed across the surface until all of the rings were filled level with the top.”

TriVitro Corp. settled in Seattle, WA, in 1996 as a manufacturer of 100% recycled glass. Vitrohue tumbled glass is recycled from waste glass made from post-consumer container glass such as beer bottles, liquor bottles, scrap windows, and construction demolition glass. In addition to terrazzo flooring, the glass is used in green roof designs, fountains and water features, mosaic tiles, shower surrounds, and other artistic recycled designs.

A layer of sand underlies the Gravelpave2 and glass. “After the sand was put back in place, they could just roll out the geogrid and backfill with the crushed bottles,” says Piersol.

The total area of the Sky Lounge is approximately 1,800 square feet, with the geogrid and glass area totaling 1,000 square feet. Invisible Structures delivered the Gravelpave2 in rolls 6.56 feet by 65.6 feet. It was rolled out over the sand base and anchored with the fasteners provided with the product. The units are 100% post-consumer recycled HDPE/LDPE and can be filled with gravel or recycled tumbled glass of uniform size. The ability to roll out the flexible geogrid decreases the time, and therefore expenses, of installation.

“Initially, the intent was to install the glass loose, without any type of topping,” says Stevenson. “Due to the amount of traffic across the surface every day, some of the glass was being picked up on peoples’ shoes and tracked outside of the lounge area. We then contacted a terrazzo specialist to remove the glass, using a vacuum cleaner, stockpile it, and then mix it with a clear, non-yellowing epoxy and reinstall it into the rings. This pretty much eliminated the tracking of glass outside the area and still maintained the drainable properties.

“Where the material spanned across the concrete seating bases, it was fastened with Tapcons [screws],” he continues. “The material spanned from end to end and side to side of the recessed area. The top of the rings finished flush with the surrounding concrete walkways. The joint between the perimeter concrete walkways and the Gravelpave2 was covered with a 6-inch-wide aluminum expansion joint cover bedded in mastic and fastened to the concrete with sleeve anchors.”

Rovira says there were a few challenges with the floor. “We initially tried to secure the glass with an epoxy resin, but over time, the resin did not hold, so we periodically top out and spread additional crushed glass to cover any work or uneven areas. The space has become quite popular, and more than 13,000 students traverse the space every semester. Because we added many new electrical outlets and boosted the Wi-Fi signal, students use the courtyard more than they ever had. Consequently, the wear is more than it ever was, so we usually do the filling and grading tune-up before the semester starts and at the end of the semester in time for graduation pictures, since the Sky Lounge has become a very photogenic spot for our graduating students and their families.”

When the project began, the area was a combination of a large concrete slab and open planting areas. Stobs Brothers crews began by saw-cutting and removing the concrete to align with the perimeter columns. “The existing subgrade was mostly compacted lime rock,” says Stevenson. “It was graded and compacted to 95% density 3 inches below the final grade elevation, which is the existing walkway. Two inches of sand screenings were placed over the lime rock, compacted with plate compactors, and screened level.”

There are two aluminum seating pods within the lounge area. The construction crew placed a 4-inch-thick concrete base under each one, matching the diameter of the pod. “Electrical outlets were installed in surface-mounted boxes on the concrete bases. The finished elevation of the bases matches the elevation of the sand screenings. The Gravelpave2 was installed over the sand screenings and concrete seating bases,” says Stevenson.

The maintenance for Gravelpave2 over a 15- to 20-year lifespan is minimal and can provide extra savings over hard paving materials that might need resurfacing. At the Sky Lounge, the maintenance is done primarily by the FIU housekeeping staff.

“Future maintenance is minimal, if any,” says Stevenson. “Any area requiring replacement of glass that may be dislodged can be done easily with additional glass and epoxy. The housekeeping department uses leaf blowers to blow the surface clean of any debris. The glass surface and surrounding concrete walkways are periodically pressure-washed.”

Logistics always seems to be a challenge at construction sites, and there was nothing atypical about the Sky Lounge project. Stevenson says the walkways had a textured surface topping called Spray-Deck. It was necessary for them to be protected during the entire project. Additionally, a challenge was equipment access.

Finished in 2014, gleaming with the Florida International University school colors of blue and gold, the Sky Lounge has become a university icon.

A Green Roof at Music City Center

In Tennessee, the 2013 Governor’s Environmental Stewardship Award in the Building Green Category went to the Music City Center in Nashville. The 1.2 million-square-foot building includes three distinct green roof sections. In addition to the massive roof sections, the building has a 360,000-gallon reservoir, designed to capture rainwater to irrigate outdoor landscaping and to flush the center’s toilets. These features helped move the building toward LEED Silver certification, according to North Carolina-based Bonar Building and Roofing.

In a world where massive construction projects dominate, this cultural icon in Nashville’s SoBro district will compete. The main roof area, with an 180,000-square-foot green roof, presented some challenging characteristics. A rolling surface with pitches ranging from 16–25% provided the greatest challenge for keeping the green roof media stable.

Charlie Miller, president and founder of Roofmeadow, specified Enkadrain W 3601 by Bonar be installed as underlayment and drainage system for the roof’s organic materials. “We want to preserve moisture in the system but prevent soggy or anoxic conditions,” he explains. “It’s thin enough so that it does not impede root growth through it and down to the capillary fabric. Filaments will entangle roots, enhancing the structural integrity of the entire system.”

To continue reading the full article, which includes additional case studies and in-depth reporting, check out the March/April edition of Erosion Control. Please click here. You may need to log-in or subscribe to our magazine.